Gabriel and Magdalena: Our city became a canvas and story was painted

Gabriel and Magdalena

Gabriel Roland, director of Vienna Design Week, and Magdalena Hiller, a corporate lawyer, are long-time friends who share a passion. That passion is for the art and mosaics displayed on the buildings of Vienna. One day, they decided to share their love for this unique type of art with all of us and created the Museum of Looking Up.

Das Museum des Hinaufschauens Instagram

Where did your passion for facade art and mosaics come from and why did you create the Museum of Looking up?

We are two people enthusiastic about living in Vienna. For a long time, we were sending each other pictures of interesting facade paintings or mosaics from all over the city. While sitting at home during the pandemic, we were like now is the time to act! Museums were closed, but there was still so much to look at outside. So why just stare into your phone?

We also wanted to motivate people to see our city in a different way. Most tourists see Vienna as this imperial, turn of the century Disneyland, but that finished in 1918. Vienna kept evolving and the times that followed are also important parts of the urban fabric.

Lots of art on the facades was created during the social housing era in the 1920s, but also during the fascist times and after the war. Our city became a canvas onto which its political story was painted.

“Most tourists see Vienna as this imperial, turn of the century Disneyland, but that finished in 1918.”

Is this one of the reasons why — when collecting “city art” — you are focusing mainly on the period between 1919-1989?

Yes, but there are many more reasons. As I said, Vienna is most famous for its historic 19th century buildings with opulent facades and decor, but that was mainly architecture. With the regime change from monarchy to republic, there also had to be a stylistic change. We had to do things differently, we had to build differently because we were living differently.

Social housing needed to be improved and new buildings became part of the city image program. Putting art on buildings, in turn, manifested that city and communicated how social housing was improving the city.

Then after the war the city needed to be rebuilt. Buildings were built quickly and simply, which left space for art. City incentives supported the art and for many artists, not necessarily transformational talents, it was a way to make a living.

As architecture evolved, art and architecture grew apart, and as 1989 approached, yet another political change came for Vienna, a city on which the Iron Curtain had a big impact. Plus, we wanted to draw a line between street art, which needs to be looked at separately.

Do you think that people enjoy this type of art or is it looked at as something obsolete that belongs to the past?

People usually enjoy it. They say, “that mosaic is nice and colorful, but there isn’t much context behind it.” Most of these art creations are simple and feature flowers or deer. It is art that is easily digestible without lots of thinking. You can just walk down the street, look up and enjoy it.

People notice it on some subconscious level, but they might not even realize when it’s gone. That’s where we come in. Through research and story telling we are able to raise the public’s awareness and understanding of these pieces of art on the buildings surrounding them.

“It is art that is easily digestible without lots of thinking.”

How do you source all the information to get the full picture behind each piece of art?

Sometimes we know immediately because we recognize the style of the artist, but in other cases, it can be very difficult. It’s complicated but a very fascinating situation. It’s totally outside of the usual mode of appreciating art.

If you look at these art pieces from a relevant art history, they are not included. Theses artist were on the edges of the art scene. But they are definitely historically relevant because they were able to integrate their style and vision upon the city in their very personal, but unobtrusive way.

“If you look at these art pieces from a relevant art history, they are not included. Theses artist were on the edges of the art scene.”

Do you have a favorite piece of art or artist?

Magdalena and I are big fans of an artist named Franz Molt. He is a great mosaic artist, who creates bodies and volume from random seemingly bits of tile. One of his pieces was this futuristic vision of Vienna with a motorway, helicopter and cathedral in the middle, but it was sadly removed.

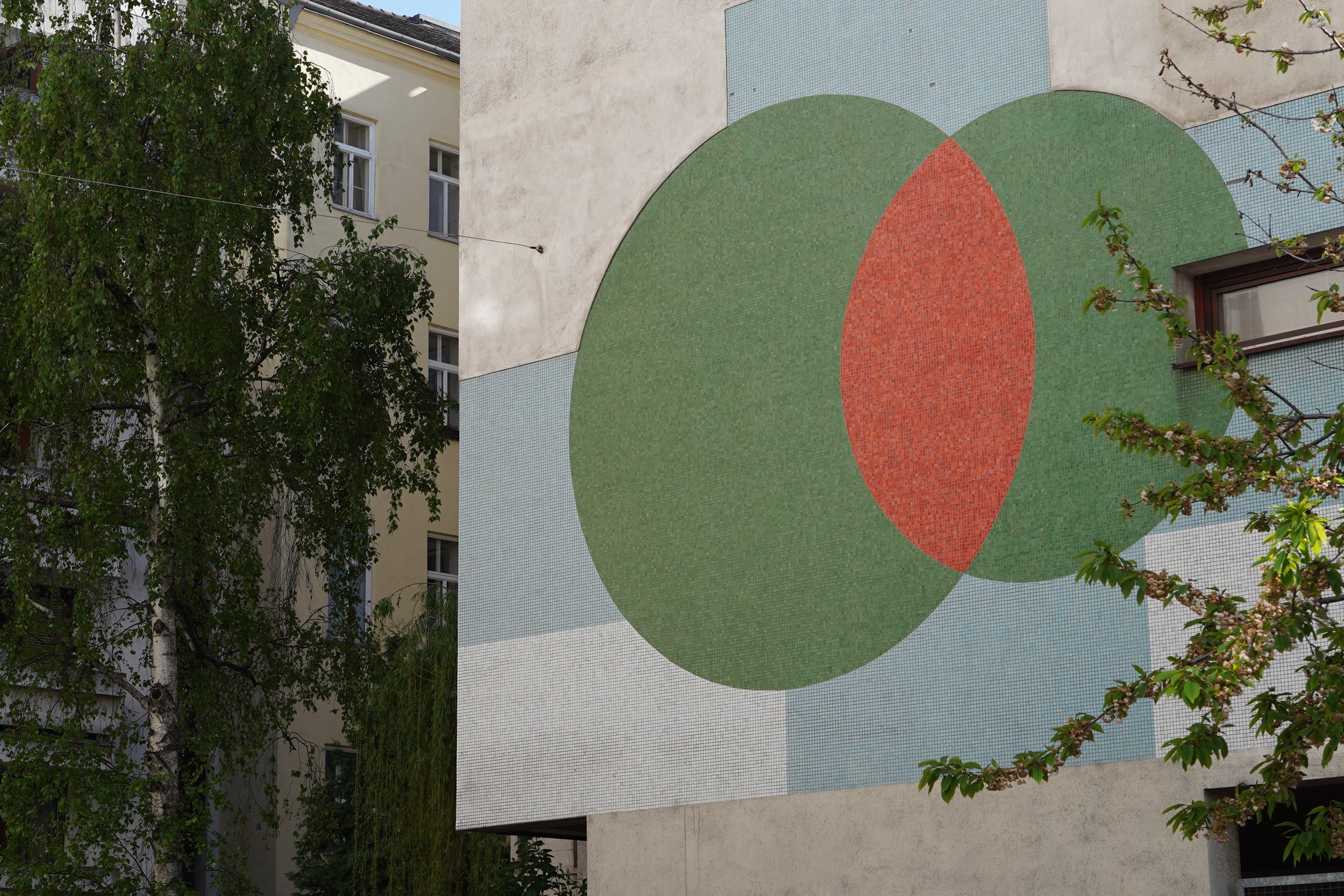

I also enjoy an abstract artist named Alfred Kirchner, who created these interesting circles in very beautiful colors. But, of course, there are many others that I enjoy.

Are these art pieces protected? How does it work when a building needs to be renovated?

It’s very unclear. How is the city supposed to protect something that they don’t even know exists? But people are more aware these days, and at the same time, these pieces become older.

We were lucky to witness the process of a mosaic being taken down and glued back on. Funny story actually. We were walking by this mosaic regularly, and all of the sudden it was gone. We were ready to fight — already drafting a not very nice email — but came to find out it had been removed for restoration. It was fascinating to see it up close and to be part of the process of returning it to its original glory.

Starting this project — the Museum of Looking Up — we now have the responsibility to protect these pieces.

Unlike a traditional museum, you always have to find your pieces. How about when you run out?

Museums in Vienna have so many great pieces but the majority of their collections is usually hiding somewhere in storage. That’s the complete opposite of us. We rely on our great community to send us pictures and notify us about new pieces.

But to be a museum you have to not only have a collection, you also have to communicate, do research and protect the pieces. Those are the elements that make you a museum. If you are doing just exhibitions, you are an exhibition hall. If you conduct only research, you are a research institute. And, if you only conserve, you a restorer. We have to aspire to be all four of these things.

Of course, the more pieces I have seen the less new ones I see, but there is still so much to be discovered!

“Museums in Vienna have so many great pieces but the majority of their collections is usually hiding somewhere in storage. That’s the complete opposite of us.”

What’s something new you learned while on this journey?

A lot! For instance, this connection between political history and art that is immediately projected into the city, that is something I didn’t realize until I thought about it. Now I am more aware.

We need these elements in the city. I am not necessary saying that it has to be art, but anything that we can attach ourselves to. Accumulation of buildings does not make a city, it needs to have something extra in between. For me, these pieces are an example of such an element. They add a local identity.

“Accumulation of buildings does not make a city, it needs to have something extra in between.”

How do you see the Museum of Looking Up evolving? What’s next?

It all started as a passion and we could not have done this without our community. We rely on them a lot. But with this comes responsibility. Of course, we are thinking about the future of our project and how to professionalize it.

Recently, we had our first guided tour and received a grant from the Vienna Business Agency to create a publication so more people can find these pieces. Our goal is to create a series of hyperlocal leaflets working with local photographers and designers. We want it to be more than just a piece of paper. We want it to be part of the community.

So as you see expectations are big and so are the plans. But we always want keep the joy that was at the very beginning of it all.

All photos ©Raufschau Museum